A nasty trick on musicians.

Mapping modes section added April 2025

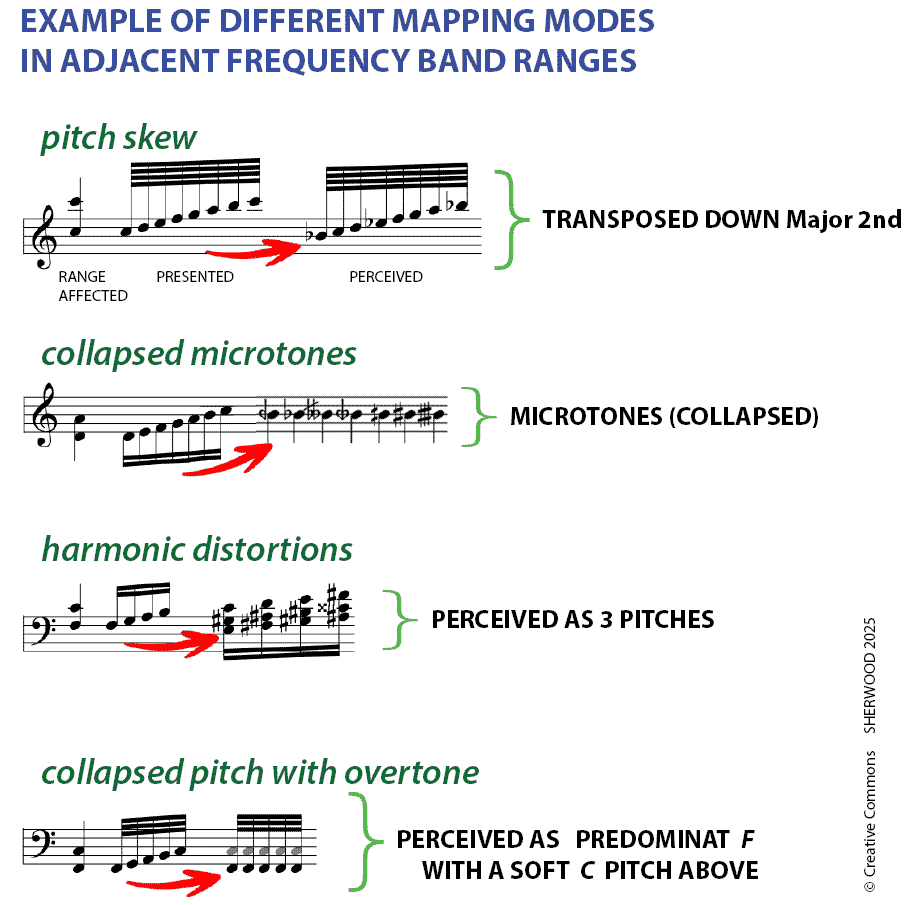

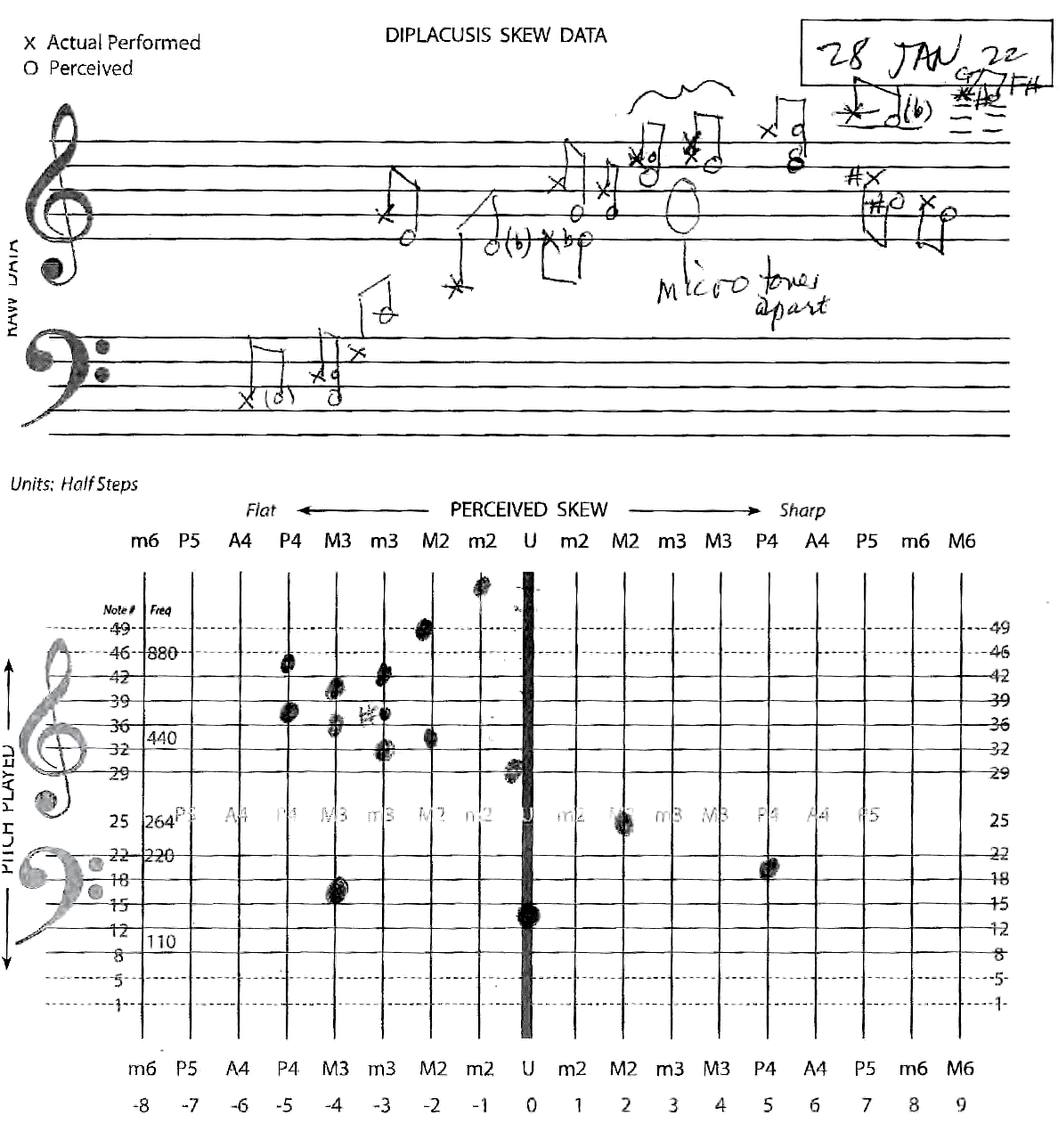

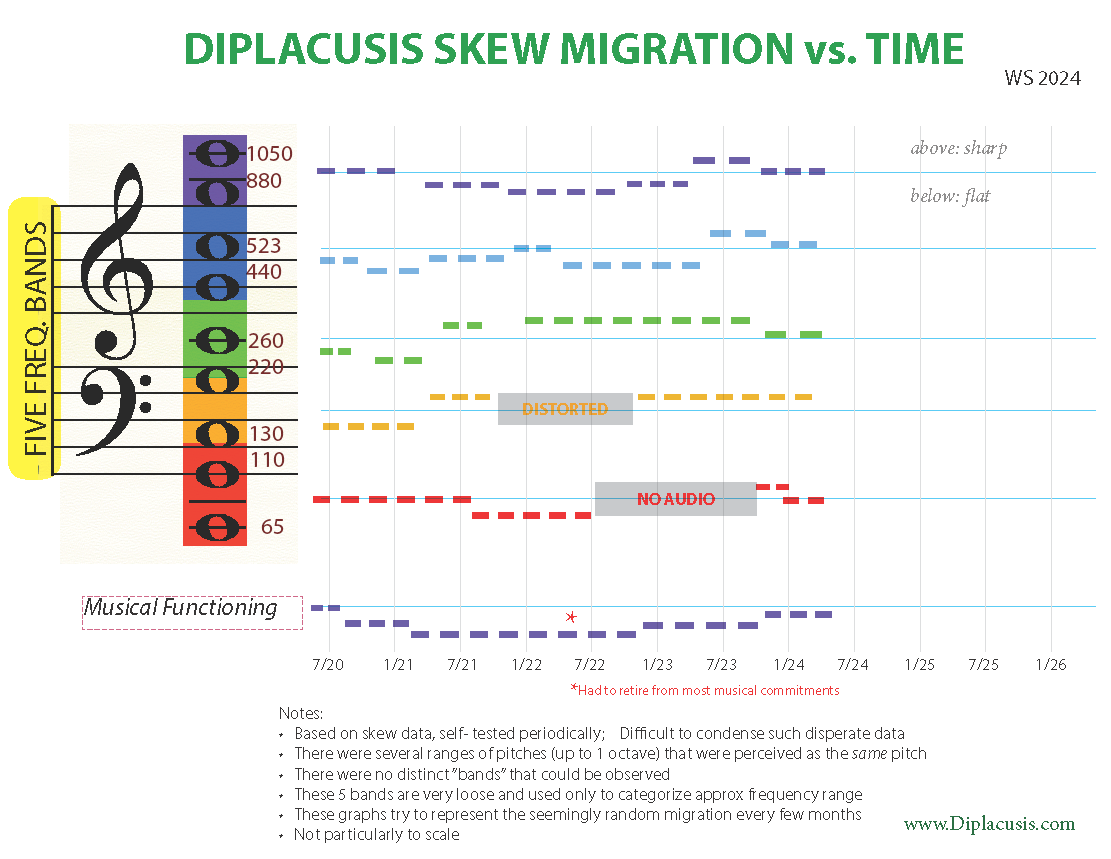

For a given ear at a given point in time, an affected frequency band (range of pitches) could have one of these mapping modes, while other ranges might have no alterations at all, or even a different skew interval or a different mapping mode mechanism. Over time, both the range boundaries/extents and the mapping modes can slowly change (morph over a period of months).

Homage to Larson . . .

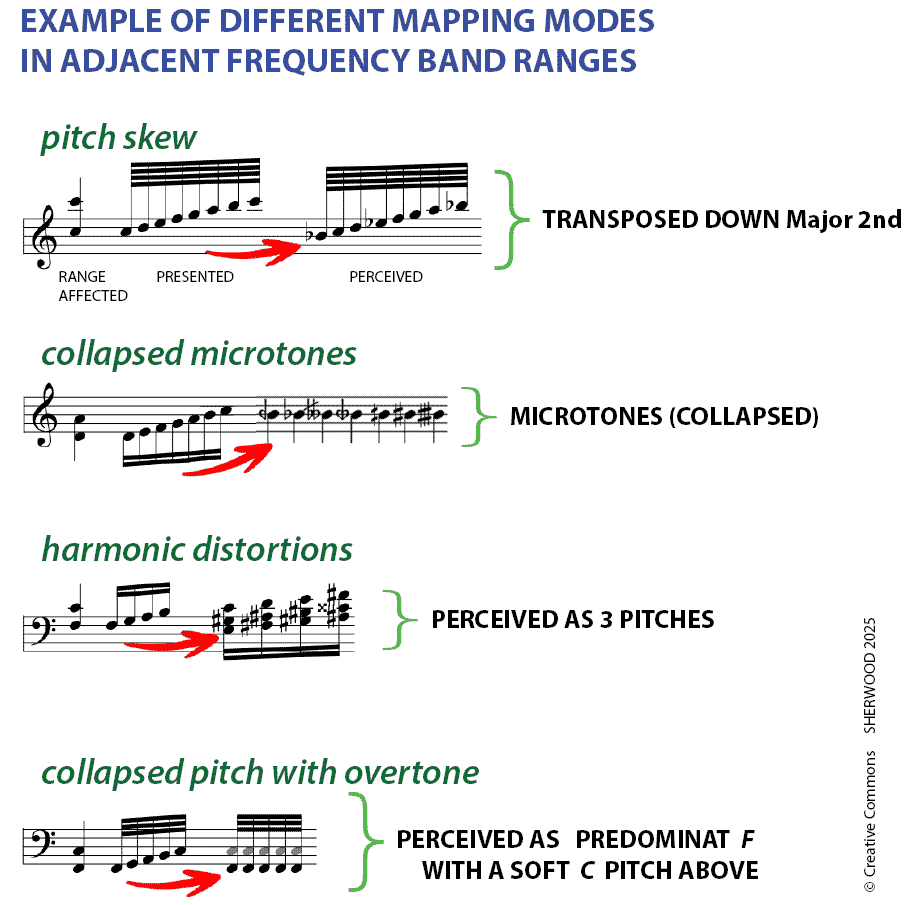

Diplacusis, also known as disharmonica or interaural pitch difference (IPD), is a hearing disorder whereby a single auditory stimulus is perceived as different (or distorted) pitches between the ears. Sufferers may experience the effect permanently, or it may resolve on its own either temporarily or permanently. Diplacusis can be particularly disruptive to individuals working within fields requiring acute audition, such as musicians, sound engineers or performing artists.

Actual experience - just as the brain's plasticity starts to "accept" the pitch discrepancies and begins to adjust to perceive sound as less distorted, the pitch skew changes/morphs/migrates and sounds uncomfortably distorted anew. In this case, this was accompanied by an increasingly expanding array of tinnitus sounds (proverbial whistling/squealing, aviary/crickets, steady pitches/clusters (cf. pipe organ mixture ranks), notch-filtered white noise) all on top of the chronic (forever) high-pitch cluster (8K-10K). Diplacusis can be a creative source for improvisation - the "wrong ear" might hear a new key/modality to jump to that leads the performer to change keys or introduce various compositional devices/treatments. (See discussion below of Charles Ives who sometimes composed in two keys simultaneously)

Some pitches present as multiple pitches as if a harmonic-rich/complex sound (sometimes including a faint original pitch, many times not).

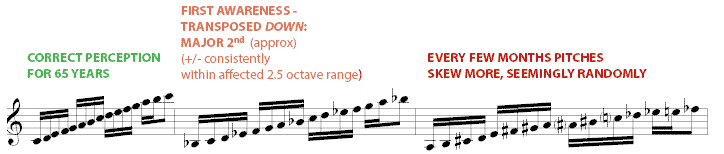

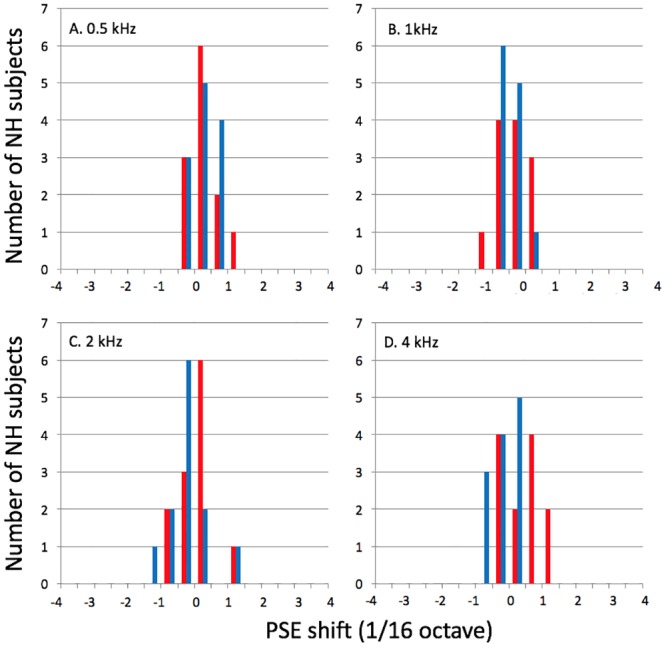

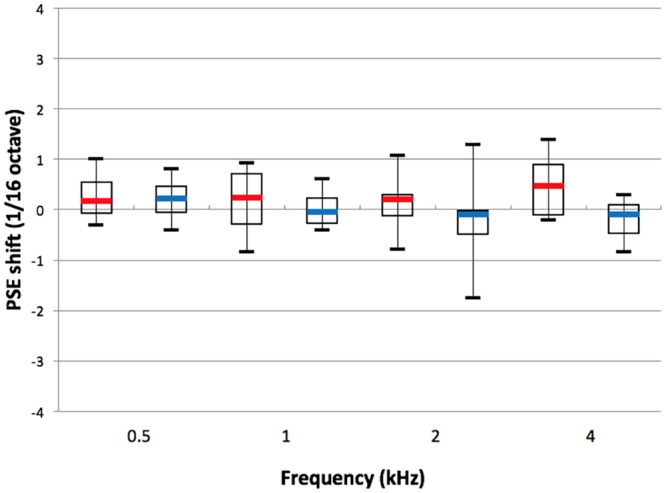

Some research studies focus on the frequency range where the slope of the ear's audiogram results is steeper at the hearing loss frequency. However in the above experience, the perceived pitch shift was across the spectrum (and the skew shifted as time progressed).

Note that audiograms measure only that "some pitch(es)" are perceived (or not) at each presented frequency. With diplacusis, the perceived pitch (or multiple pitches) will likely not be the intended frequency. In the case of tinnitus on top of all this, it's often helpful to have the audiogram pitches presented as "trills" or "warbling" in order to sort out the presented pitch from background tinnitus.

Apparently the most common mapping mode is pitch-skew transposition, which usually has a consistent interval offset within a range (perhaps a range of 1-2 octaves affected). A separate range may have a different interval-distance and/or direction.

One wonders if diplacusis is why some people cannot "match pitch" (how to know which ear is "correct"?!) or maybe having the condition stimulated some composers to write in two keys at once.

For some pitches, the perceived tone can be so distorted, there is no identifiable pitch.

YouTube demonstration for one manifestation for pitches collapsed as microtones. (Grazie molto a Giacomo Favitta, maestro di musica Italiano)

Research References Nature.com article (Guinan et al.)

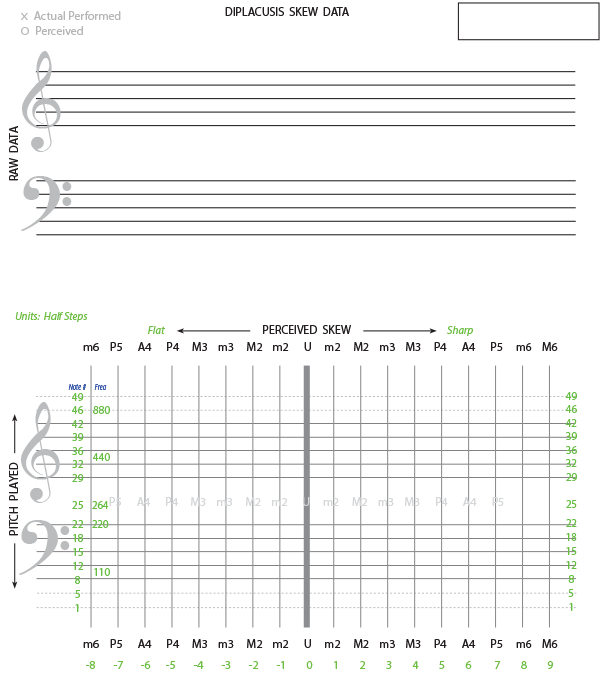

PDF blank chart to record pitch skew

(the green "units" on the vertial axis are half steps starting a low CC, such that the data can be quantized in excel or a database for tracking changes over time)

Often one performed pitch is perceived as multiple pitches or a predominant pitch with unusual overtones (or distortions)--these are difficult to represent on a music staff.

Sometimes several contiguous halfsteps would be perceived as he same note, or perhaps JND microtones apart.

In addition, perceived pitches do not quantize to a western music equalt temperament frequency--microtones are often perceived.

Unfortunately, no digital signal generator was use to match pitch frequencies precisely.

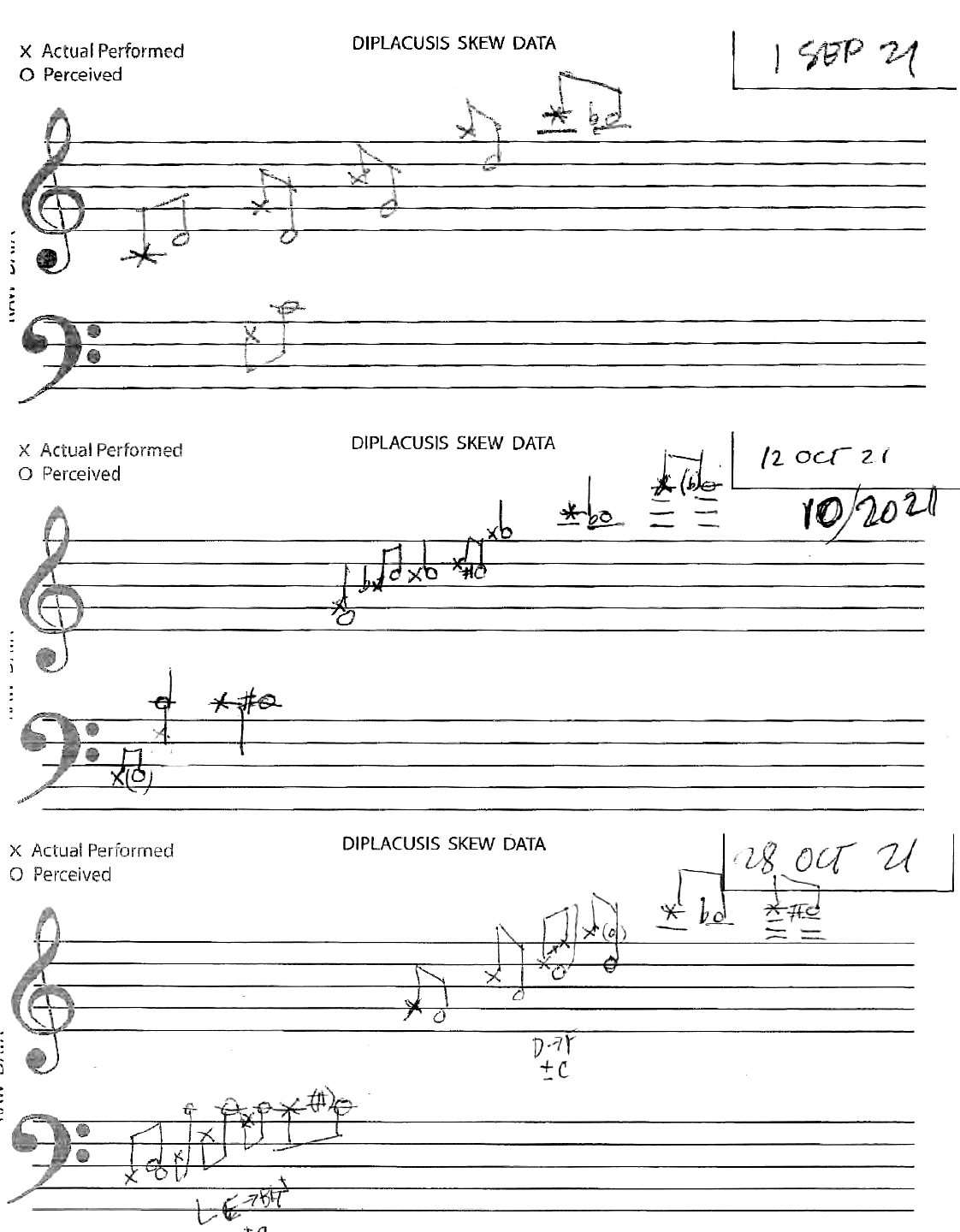

Amazingly, diplacusis skew & direction can drift over time (months). Below is an approximation of skew per band over time.

Still seeking a format/method for tracking the non-trending skew data over time.

(FWIW first graphing sketch in search of a format)

(Piano transcription excerpt, Ives: Variations on 'America') Right hand and left hand key signatures are a Major Third apart, which is still somewhat tonal.

Diplacusis is a condition in which a person perceives the same sound differently in each ear (or different from physical reality), often experiencing a distorted or altered pitch. This can occur when there is a difference in the way each ear processes sound (or the brain or auditory nerve processes sound), leading to a dissonance between left and right auditory perceptions.

There are speculations and anecdotal evidence suggesting that Charles Ives, an American composer known for his innovative and experimental approach to music composition, may have had diplacusis, or a related auditory condition.

Here are several factors to consider when exploring this possibility:

1. Ives' Unique Musical Style:

Ives is often celebrated for his groundbreaking use of polytonality (simultaneous use of different keys), complex rhythms, and dissonant harmonic structures. These characteristics in his music might suggest that he had an unusual perception of sound. Some of his compositions, such as "The Unanswered Question" or his symphonies, feature layers of sound and shifting tonalities that could be seen as mirroring what someone with auditory perception differences, such as diplacusis, might experience.

2. His Personal Experience with Hearing:

Ives had some hearing difficulties throughout his life. In his early years, he had a tendency to experience a heightened sensitivity to sound, which could be indicative of an auditory processing disorder. Additionally, there are reports that he had difficulties with pitch recognition and sound differentiation, which are often symptoms of conditions like diplacusis.

However, it is important to note that Ives himself did not publicly claim to have diplacusis, and any medical diagnosis of this nature would be speculative at best. His hearing issues may have also been related to other factors, such as his exposure to loud environments during his time working in insurance or his experiences with illnesses like a bout of mumps that affected his hearing.

3. Potential Impact on His Music:

If Ives had diplacusis or a related auditory condition, it could have contributed to his unconventional approach to harmony and rhythm. Diplacusis might cause a composer to perceive intervals and chords differently, potentially leading to the creation of music with unusual or unpredictable harmonic relationships. This could help explain Ives' sometimes jarring, but innovative, musical constructions.

4. Historical Context and Diagnosis:

During Ives' lifetime (1874–1954), there was less understanding of specific auditory disorders like diplacusis, and it is unlikely that Ives ever received a formal diagnosis. He might not have had the language or medical support to articulate his auditory experience in terms we would recognize today.

Conclusion:

While it is impossible to definitively diagnose Charles Ives with diplacusis without medical evidence, there are intriguing connections between his reported hearing difficulties and his distinctive musical style. His innovative use of dissonance, complex textures, and unusual harmonic choices may suggest that he experienced sound in a way that was different from the norm, potentially due to a condition like diplacusis. However, it is important to treat such speculations with caution, as definitive proof of such a condition is lacking, and many factors could have influenced Ives' compositional choices. He could have just been having fun!

. . . and assuming the subject is a musician or understands pitches & intervals.

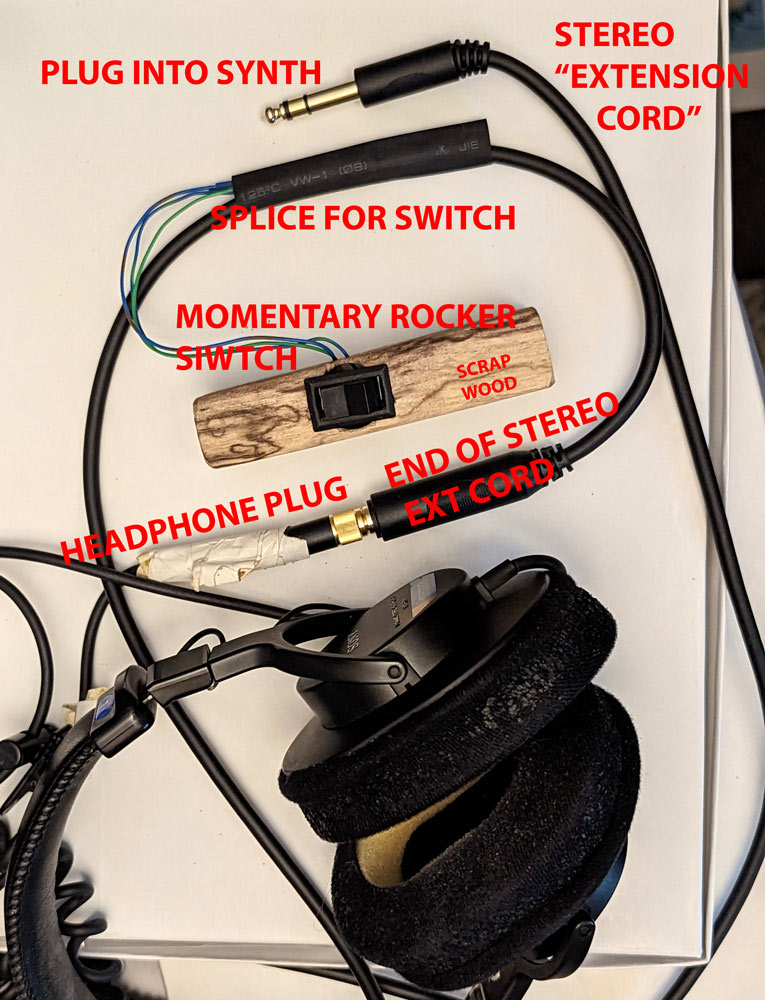

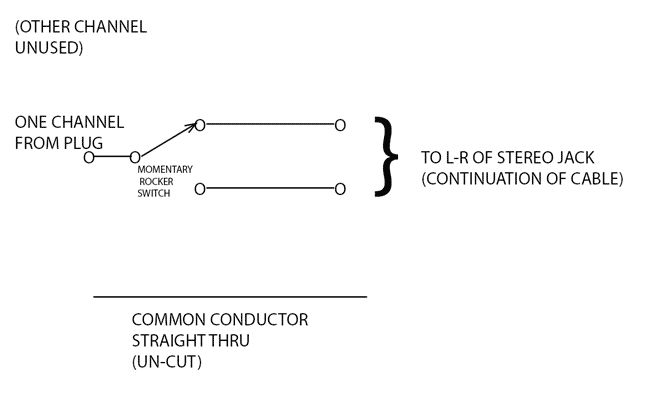

Prepare an audio patch cable that has an inline momentary switch to select which ear receives a (common) pitch played on a keyboard (synthesizer).

We've found that a pure tone (bass flute or organ flute -- closest to a pure sine wave) patch works best since any overtones/partials can confuse the pitch perception.

Go thru a range of pitches (every fifth or third) and for each test pitch -- present to the bad ear first (so there will be minimal biasing for what the actual pitch is), and then to the good (control) ear.

This depends on the musical training of the subject to discern the relative pitch perceived in the bad ear.

Amplitude has not yet been considered, altho loudness seems to influence the perceived pitch (seemingly not akin to the psycho-acoustic perception effect that louder pitches sometimes seem slightly sharp/JND).

Sometimes the bad ear perception even for a single pitch is so distorted it is perceived as a complex tone with enharmonic partials. No convention has yet been devised to notate the various partials other than a stemmed chord notation to notate all partials perceived..

The data form has evolved over the years to facilitate ease of data capture and detail needed.

Schematic for above patchcord/rockerswitch: (stereo common/shield is passed through)

IMBALANCE SEVERITY SCALE AND EPISODES - "Vestibular Migraine"